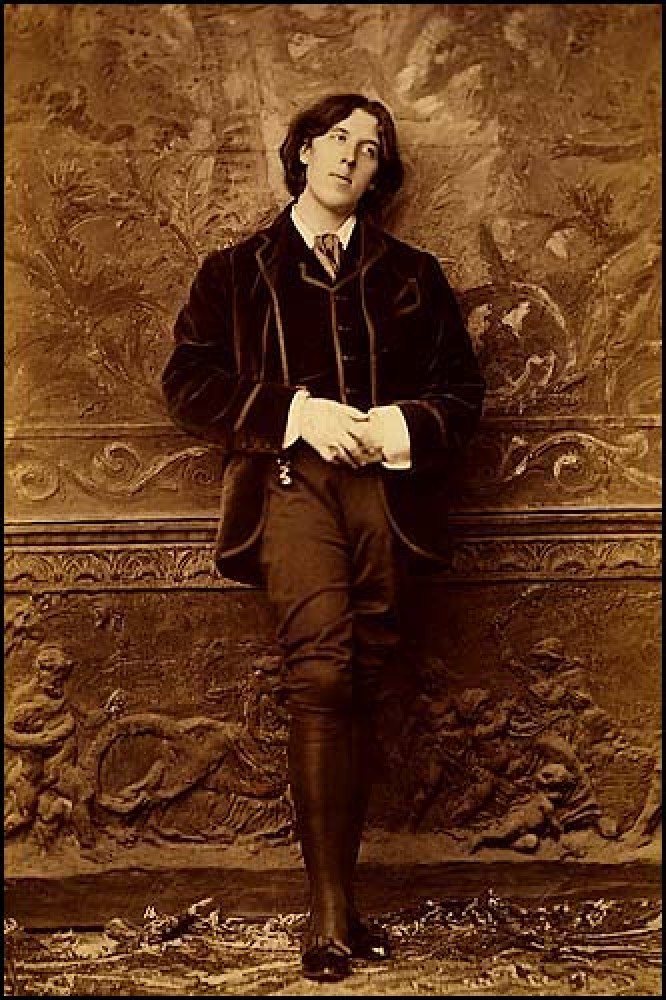

As an academic who specializes in Victorian literature and a steampunk who enjoys taking on the persona of Dorian Gray on occasion, I get a lot of questions and not a few strange looks from my colleagues and students when I explain what steampunk is (or at least try to) and why I so thoroughly enjoy being part of this subculture and avidly devour its fiction. Though most people are definitely interested in steampunk or pretend to be for my sake, I often get the sense that they wonder why a “serious” academic like myself is interested in steampunk culture and literature – that I have crossed some sort of academic nerd line in the sand and may be slightly strange for doing so.

What this attitude misses is how speculative fiction and the subcultures that embrace it, most especially steampunk, can welcome diversity and difference in ways that rare in mainstream culture and give both energy and verve.

Given that speculative fiction questions our most basic assumptions about life, from what is the nature of consciousness to our knowledge of history, it also regularly challenges our accepted ideas about gender and sexuality. As heated debates around these subjects across the globe suggest, how we define gender identity and sexual orientation are particularly thorny issues because they are at once deeply private and personal as well as intensely public and cultural. Because speculative fiction takes us to imaginative worlds that may be in another galaxy or, closer to home, an alternative version of our world, it has more freedom to explore such issues. Indeed, some classics of genre, like Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Left Hand Darkness, can go so far as to wonder how we might interact with a world of people who have no gender and whose sexuality is fluid and changeable.

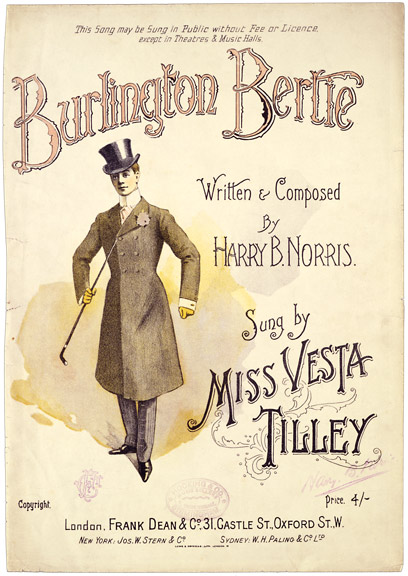

And, it is in this arena, dear readers, where steampunk does such delightfully interesting things. Since steampunk takes as its “raw materials” nineteenth century literature and culture, it has the ability to offer alternative ideas about a number cultural concepts that we may take for granted, including sexuality and gender. In the nineteenth century, we find the beginnings of so many parts of our Western culture’s ways of talking about these issues. To name but a few:

And, it is in this arena, dear readers, where steampunk does such delightfully interesting things. Since steampunk takes as its “raw materials” nineteenth century literature and culture, it has the ability to offer alternative ideas about a number cultural concepts that we may take for granted, including sexuality and gender. In the nineteenth century, we find the beginnings of so many parts of our Western culture’s ways of talking about these issues. To name but a few:

|

Because so many of these cultural ideas and institutions are being hashed out during this time, they’re often a bit untidy, giving us the ability to see the inner workings and motivations of why these concepts became what they are today. |

Consequently, when steampunk turns its clockwork hand to reimagining the nineteenth century, it can create a deliciously flexible space for sexual and gender identities that still trouble our society today. Much like a seamstress ripping out stiches on a garment and putting it all back together again with a few key additions that entirely alter the effect of the item, steampunk takes apart the nineteenth century to see what makes it tick and then, turning it just so, gives us a transformed and newly unfamiliar past and present.

Subculture Intersections: Sex, Sexuality, and Gender Identity in U.S. Steampunk Communities

Within the steampunk community, this space allows for the challenging of gender and sexuality norms. In my experience, LGBTQIA (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex, Asexual) people are a clear minority within the steampunk community. However, while we may not have the visible presence that we ought to, we are indeed welcome and considered valued members of the community. For example, many steampunk women have a longstanding love affair with corsets, but, equally important here are the women who crossplay masculine personae, like myself, and the many men who have similar fondnesses for corsets and wear them exquisitely well.

Within the steampunk community, this space allows for the challenging of gender and sexuality norms. In my experience, LGBTQIA (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex, Asexual) people are a clear minority within the steampunk community. However, while we may not have the visible presence that we ought to, we are indeed welcome and considered valued members of the community. For example, many steampunk women have a longstanding love affair with corsets, but, equally important here are the women who crossplay masculine personae, like myself, and the many men who have similar fondnesses for corsets and wear them exquisitely well.

Indeed, the steampunk community pushes at the boundaries of mainstream notions of sexual pleasure. The extraordinarily talented Lady Clankington’s pistols enable steampunk women to enjoy the pleasure of the flesh on their own and provide steampunk men with the opportunity to be on the receiving end of penetrative sex with all the stylishness of the steampunk aesthetic. Similarly, projects like “A Steampunk’s Guide to Sex” define sex very inclusively, incorporating BDSM practices and “alternative sexualities.”

However, I would like to add that while I have personally felt very comfortable within the steampunk community as a queer cisgender woman, I do also think that the community needs to continue its conversations on gender identity and sexual orientation and to keep asking itself who isn’t at the steampunk table and why. As Ashley Rogers describes so well in discussing trans*people in steampunk: “Trans folks are on the whole accepted, though not understood and, at times, not encouraged. This is something that can change, and is en route to change yet at the moment we still deal with a lot of double standard BS that cis-gendered (labeled one gender at birth and has no intention of questioning said gender) folks never need to think about.”

For example, if steampunk events want to be truly welcoming of *trans people, they need to think about the needs of this part of the community. I would especially like to see gender neutral bathrooms become a regular part of all steampunk conventions so that *trans people at these events can use con facilities without be questioned about their gender identities.

We have begun this discussion in convention panels and more informally, and we need to continue it.

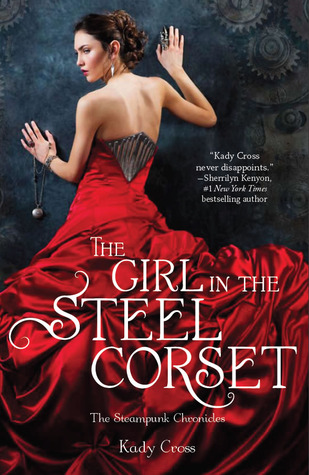

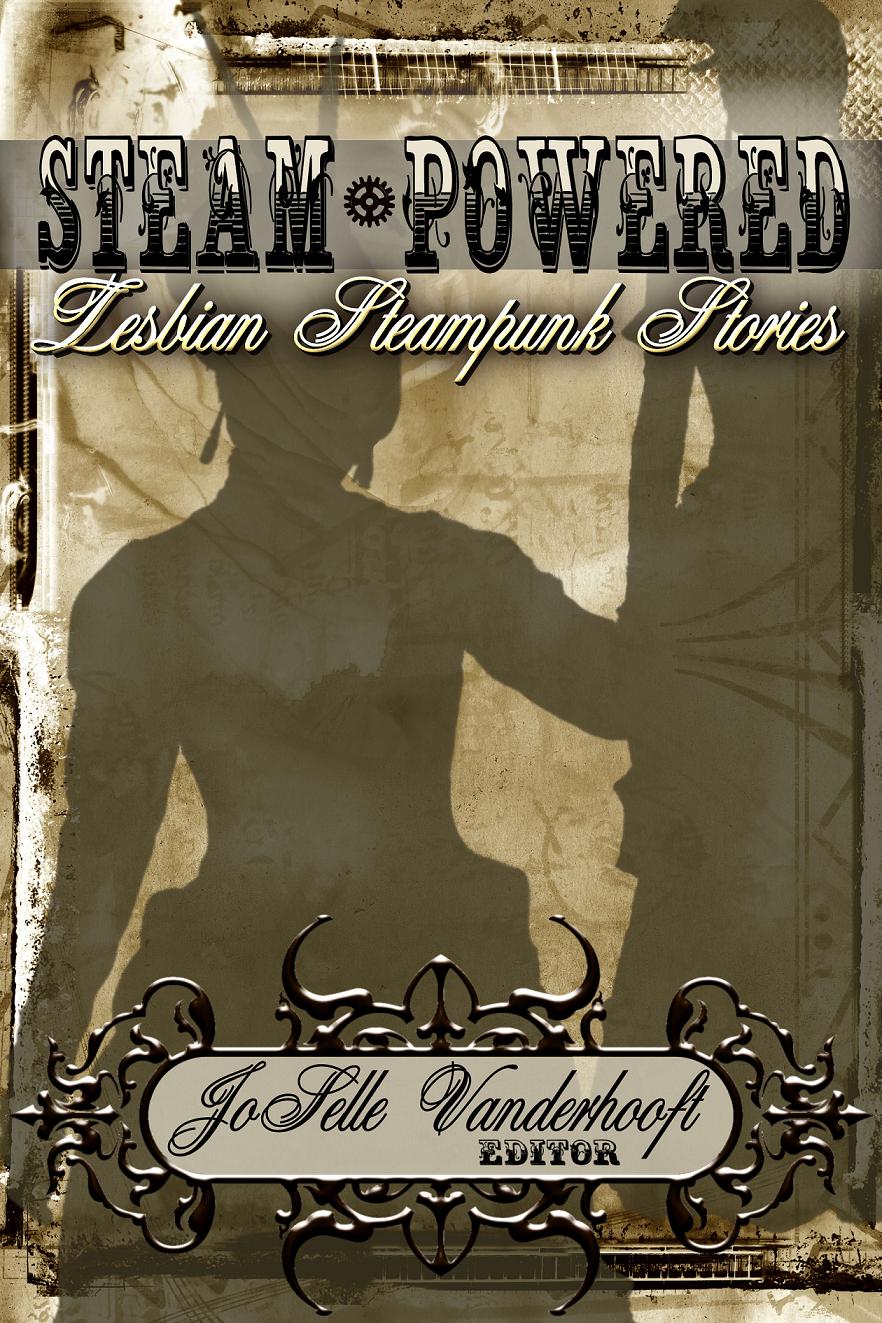

Reading All About It: Transgressive Gender Identities & Sexualities in Steampunk Fiction

In a variety of genres, steampunk fiction’s revision of nineteenth-century social norms not only gives it the opportunity to depict a variety of gender identities and sexualities – it also often serves to make its readers aware of the limits placed on those identities in mainstream culture by highlighting the gulf between its fictional worlds and our own. Picking up nineteenth century controversies regarding the role of women in society and homosexuality as a recognizable identity that seem eerily similar to contemporary debates, some of the best writers of steampunk fiction highlight the restrictions placed on women and make the subversion of those rules central to their novels and short stories. The list below (though by no means exhaustive) suggests some of the ways in which this questioning works in steampunk fiction:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

As these books and others like them exemplify, steampunk fiction, much like the subculture of which it is core part, has the ability to tell stories that might otherwise remain silenced within American mainstream culture – stories that we all need to hear.

As I draw this discussion of sexuality and gender identity in steampunk to a close, I am struck by how much I don’t know about steampunk’s rich literary, cultural, and social landscape. I am keenly curious to know how these concepts play out in books I haven’t read, languages I can’t read, places I’ve never been, and groups of people I haven’t met – a curiosity I hope that you, dear readers and fellow steampunks, can help me satisfy in offering your opinions below.

Lisa Hager is Assistant Professor of English and Women’s Studies at the University of Wisconsin–Waukesha. Her current book project looks at the relationship between the New Woman and the Victorian family. Lisa is the managing editor for the Journal of Victorian Culture Online, and her work on steampunk and Firefly is featured in The Philosophy of Joss Whedon. She enjoys wearing apocryphal green carnations at steampunk conventions and has a long-standing affection for difference engines and Ada Lovelace.